International touring exhibitions have become a regular fixture at major cultural institutions across the globe. They are, perhaps, the most complex, large-scale, expensive and specialised work in contemporary museums. Despite their growing popularity, investment and professionalisation, surprisingly little research has been undertaken to better understand why and how international exhibitions are organised, and what value they have. This article presents new ideas about international exhibitions that have emerged from our extensive research on the subject, recently published in the book Cosmopolitan Ambassadors: International exhibitions, cultural diplomacy and the intercultural museum (Davidson & Pérez Castellanos, 2019).

In this book we envisage international exhibitions as mobile contact zones that operate across not only geographical and cultural borders, but also on the boundaries of museum practices. With international exhibitions, it is not only objects that are mobile, but also people—the museum professionals who negotiate, develop and tour these exhibitions in collaboration with international colleagues—who must often negotiate complex political, institutional and museological differences. Likewise, the visitors arriving to see the exhibitions engage with them through the lenses of their own particular contexts. Furthermore, these exhibitions form part of the transnational work of museums which is implicated in systems of international cultural relations and politics. Their meaning and intentions relate, therefore, not only to museum missions, visitor attraction and enlightenment, but also to national and international diplomatic agendas. These forms of encounter and associated interpretations shift as exhibitions move between different cultural contexts.

A main premise of our book is that international exhibitions involve myriad forms of cultural encounter and therefore countless opportunities for misunderstanding and mis-representation but, at the same time, significant potential for developing intercultural skills, understanding and what is referred to as a cosmopolitan imagination or outlook—deemed by many as essential for navigating the accelerating processes of globalisation within which we find ourselves in the twenty-first century. At the heart of Cosmopolitan Ambassadors is the tentative proposition that international exhibitions are a means by which museums might represent and advance a cosmopolitan agenda on the world stage.

This article explains where our ideas have come from, before outlining what we mean by cosmopolitanism and why we think it is a useful way of thinking about the purpose, practice and potential impact of international exhibitions. We then briefly summarise the main takeaways from our research.

We conducted fifty-one interviews with museum professionals [...] closely involved in the production and touring of the exhibitions.

Where have our ideas come from?

Our ideas about cosmopolitanism and international touring exhibitions have evolved from a close study of current museum practice. This has taken the form of a long-term research project focused on two travelling exhibitions involved in an exchange between Aotearoa New Zealand and Mexico.

E Tū Ake: Standing Strong was a ground-breaking Indigenous exhibition featuring both traditional and contemporary taonga (Māori cultural treasures) and developed to tour internationally by the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (Te Papa). It was shown briefly in Aotearoa New Zealand before travelling to the Musée du Quai Branly, Paris, followed by the Museo Nacional de las Culturas in Mexico, and finally the Musée de la Civilisation, Québec, Canada, between 2011 and 2013. The hosting of E Tū Ake in Mexico constituted the first phase of the inaugural exhibition exchange between the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH) and Australasia.

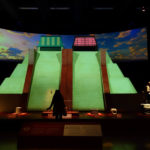

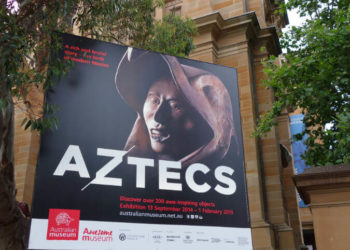

The second phase involved the development of the exhibition Aztecs by Te Papa in collaboration with INAH, and as part of a partnership with two Australian museums. Aztecs opened at Te Papa in September 2013, and then toured to Melbourne Museum and the Australian Museum in Sydney, before closing and returning to Mexico in February 2015. Aztecs involved a high level of institutional collaboration during the exhibition development stage and engaged staff across the executive, administrative and operational levels of several museums in three countries with contrasting museological, institutional and political contexts. At its centre was an ongoing relationship: the closure of Aztecs and the return of the collection to Mexico marked the end of a cycle of approximately six years of collaborative work between Te Papa and INAH as part of the exhibition exchange.

We conducted fifty-one interviews with museum professionals from Mexico, Aotearoa New Zealand and Australia who were closely involved in the production and touring of the exhibitions, including curators, concept developers, project managers, writers, interpreters, and educators. We wanted to understand how professionals in various roles from different countries worked together to develop and manage the exhibitions, the main challenges they faced and how they perceived the exhibitions’ purpose and importance. We also conducted eighty-six in-depth interviews with visitors to gain insights into their cultural encounters with international exhibitions, both short-term and long-term. This aspect of the research was informed by a rapidly expanding theoretical literature on the ways in which visitors engage in complex acts of interpretation and meaning-making when visiting museums and other heritage sites.

Some of the key questions we sought to answer were: How are museums working internationally through exhibitions? What motivates this work? What are the benefits and challenges? What factors contribute to success? What value does this work have for audiences and other stakeholders? What contribution do international exhibitions make to cultural diplomacy, intercultural dialogue and understanding and how can this be assessed?

What is a cosmopolitan outlook and what does it mean for international exhibitions?

Cosmopolitanism has a long tradition in the history of ideas, and many strands. In the context of international exhibitions, we found British sociologist Gerard Delanty’s (2006, 2011) theory of critical cosmopolitanism particularly helpful. Delanty is interested in what happens when one culture meets another and his cosmopolitan perspective highlights the transformational, creative and critical outcomes of these encounters. Underlying a cosmopolitan perspective or outlook is a “critical self-understanding” and the ability to incorporate the perspectives of others into one’s own “identity, interests or orientation in the world” (Delanty, 2011, pp. 634–635). Essentially, he says, cosmopolitanism is “a way of imagining the world” that suggests both openness and fragility, “since it rests on the bonds of mutuality and dialogue” (Delanty, 2011, p. 635).

What does cosmopolitanism look like? Delanty (2006, pp. 42–43) suggests we may find it in:

- irony (emotional distance from one’s own history and culture)

- reflexivity (the recognition that all perspectives are culturally conditioned and contingent)

- scepticism towards the grand narratives of modern ideologies

- care for other cultures and an acceptance of cultural hybridization

- commitment to dialogue with other cultures; and

- nomadism (a condition of never being fully at home in cultural categories or geo-political boundaries).

Another important quality of a cosmopolitan outlook is that rather than being either present or absent, it exists “in degrees” (Delanty, 2011, p. 648). The philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah (2006) makes the point that we should not underestimate the difficulty of understanding one another and of achieving transformation because often what changes people’s minds is “not an argument from a principle, not a long discussion about values, but just a gradually acquired new way of seeing things” (Appiah, 2006, p. 73). Because of this, cosmopolitan engagements with the experience and ideas of others are valuable in themselves, regardless of whether or not any agreement is reached, as “it’s enough that it helps people get used to one another” (Appiah, 2006, p. 85).

Successful cross-cultural collaboration on international exhibitions requires museum professionals to develop an intercultural museum practice underpinned by a cosmopolitan outlook.

The idea of a cosmopolitan outlook as something that might be nurtured and developed is similar to the notion of intercultural competency, which is also described as including awareness of one’s own cultural assumptions and an openness to multiple perspectives leading to reflection and an enhanced understanding of self. Being intercultural involves curiosity, empathy, respect and tolerance of ambiguity (Gupta, 2002; Perry & Southwell, 2011; Ryan, 2002), as well as the ability “to reconstruct the others’ frames of reference and see things through their eyes” (Bredella, 2002, p. 237).

In our book, we used a cosmopolitan lens to bring into focus the transformational, creative and critical outcomes of cultural encounters involving five principal groups of actors interacting in the mobile contact zones of international exhibitions: the represented culture (past and/or present), encountered primarily through their material culture and the stories connected to it; a diverse range of professionals from the sending institution/s; professionals from the receiving institution/s; visitors to the exhibition, events and programmes, including users of digital media, and others they affect as a result of their encounters; and stakeholders, including communities, sponsors, public funders, diplomats and other public service representatives.

International exhibitions are intercultural spaces because they create situations of encounter that expose our cultural assumptions and provide us with the opportunity to either dismiss the perspectives of others or re-evaluate our own Successfully navigating these spaces requires sufficient cognitive complexity to deconstruct stereotypes—skills which can be developed over time through different experiences. We therefore approached cosmopolitanism and interculturality as relevant to both the goals and the processes of producing international exhibitions; and as something that arguably should be an integral part of all museum practice.

Cosmopolitan takeaways for international touring exhibitions

Cosmopolitan Ambassadors presents several practical takeaways that might inform the successful development of international touring exhibitions and an evolving intercultural museum practice.

Investigating how our case study exhibitions were organised, and some of the issues faced, demonstrated the importance of clearly understanding the available economic and production models for international exhibitions, and the forms of partnership these might involve. Each model has certain advantages and disadvantages, an awareness of which could enhance decision-making, reduce potential conflicts and misunderstandings, and help institutions to develop better strategies and plan partnerships that are most appropriate to their needs, resources etc.

Successful cross-cultural collaboration on international exhibitions requires museum professionals to develop an intercultural museum practice underpinned by a cosmopolitan outlook. This includes a thorough understanding of different working styles, processes and timeframes, as well as appropriate communication styles, channels and frequency. Attention to these helps ensure that staff working across differences can find intercultural solutions to common problems. This may involve re-evaluating their existing practices and the assumptions that underpin them, considering the benefits of adaptation and compromise, adopting open-mindedness, being respectful and receptive to the feelings and needs of others. Intercultural solutions take time and require willingness to talk through differing perspectives in order to create a new centre on what may have previously been a boundary, but the outcome can be innovation, creativity and transformation on both a personal and professional level.

Fostering and maintaining strong intercultural relationships is also critical to success in international exhibitions. Culturally specific formal protocols and informal practices for welcoming and hosting visiting staff can be deeply beneficial for enhancing working relationships and long-term connections.

Developing intercultural exhibitionsParticular challenges can arise around engaging audiences at the host venue while maintaining cultural sensitivity towards the country of origin. A comprehensive and cohesive intercultural engagement strategy, including object selection, design, text, graphics, marketing, community outreach, events, programming, merchandising and other commercial components, can help to mitigate potential issues. Allowing adequate time for consultation with institutional partners is also crucial in order to overcome inevitable misunderstandings and achieve cosmopolitan outcomes. Where exhibition co-development is involved, and even for less intensive adaptations, the translation of meanings between cultures can require extensive consultation. Reaching intercultural solutions requires a back-and-forth dialogue and this needs to be allowed for in production timelines.

International exhibitions are assemblages of people, objects, practices and meanings that are always in the process of becoming.

Intercultural meaning-making

Our research explored in detail the experience of visiting international exhibitions, revealing how visitors connect with the cultural other, negotiate differences and create cosmopolitan and counter-cosmopolitan meanings. We also discuss the resonances and ripples of meaning through visitors’ recollections many months after their initial visits. Understanding the ways in which visitors engage with other cultures in exhibitions can inform a design that helps facilitate these processes, allowing for different styles and preferences, as well as varying levels of intercultural competency and degrees of cosmopolitanism. Recent theories of visitor meaning-making, including affective and embodied cosmopolitan understandings, and the new concepts of intercultural mimicry and polycentral identification developed from our findings, could inform all aspects of exhibition design, marketing and events, complementing what many staff already understand intuitively. Knowing how visitors find relevance and relate exhibition themes to their everyday lives is also informative in regard to wider questions such as the value of international exhibitions, how they might be promoted and their role in cultural diplomacy.

Cultural diplomacy

International exhibitions can, either directly or indirectly, contribute to foreign policy goals and formal state cultural diplomacy. Government agendas may focus on idealistic and/or instrumental goals. The first includes aspects such as mutual understanding and dialogue, while the second, encompasses the desire to create favourable impressions, counter negative images, and advance other national interests, such as tourism and trade. In our research we mapped the broader national agendas with which international exhibitions intersect, and the role that diplomatic and other state actors play. Professionals ‘on the ground’ describe what they do—and the value of this work—in ways that can be read as forms of museum diplomacy, such as building relationships, forming communities of practice, increasing understanding and enhancing the reputations of their institutions, as well as their countries. Our findings, therefore, suggest that museums are intentionally performing diplomacy through international exhibitions, sometimes on behalf of governments, sometimes on their own behalf, and sometimes on behalf of others, such as Indigenous groups. What’s more, international exhibitions may serve all these interests simultaneously, illustrating the hybridity of museum diplomacy. It is not a question of either/or, but of both/and. And while the stated institutional intentions focus on instrumental purposes, staff themselves held unmistakably cosmopolitan aspirations.

In search of a broader set of indicators to define success

Visitor numbers and revenue generated (or lost) have often been used as de facto measures of the success (or failure) of international exhibitions. However, our research highlighted the ways in which international exhibitions are complex, multi-level and long-term projects and the impacts that they seek are often dispersed across institutional, market and diplomatic domains. Success in one domain is no guarantee of positive impact in another. To better appreciate the interplay and complexity of these factors, we developed a model of international exhibition drivers consisting of three intersecting domains: diplomatic, museum mission-related, and market-oriented. This model can be used to understand the particular mix of drivers for any specific exhibition. If these are clearly articulated at the outset of a project, and evaluated using an appropriate set of indicators, this will help communicate the value of an international exhibition to funders, stakeholders and the general public.

Some final thoughts

A more extended and comprehensive account of our research findings can be found in our book. There we also propose a new model of museums as polycentral: as places that might produce a kaleidoscopic vision of multiple centres and help to dissolve cultural boundaries by encouraging dialogue, negotiation and the search for intercultural understandings and a cosmopolitan perspective. We feel that this idea of multiple centres is a good way of thinking about international exhibitions because it describes what many are already doing, and what many others aspire to do. International exhibitions are assemblages of people, objects, practices and meanings that are always in the process of becoming. Each exhibition is momentary, existing only in that particular time and space, before moving on. For this reason, they lend themselves to playful dialogue and exploration, and the creation of new centres of shared meaning. It is this process by which international exhibitions might become Cosmopolitan Ambassadors of a polycentral museum – one that is founded on intercultural practices which do not fix cultural boundaries, but investigate the space in between them, opening up the possibility that we might understand each other a little better, in spite of our differences.

Website

For more information about our research, publications and consultancy services: polycentralmuseum.com

Book

Cosmopolitan Ambassadors: International exhibitions, cultural diplomacy and the polycentral museum (Vernon Press, 2019). Available at a limited-time 30% discount (expires July 16, 2019) for orders placed through the website (using code MFPDFMCLP on checkout): at https://vernonpress.com/book/747.

References

Appiah, A. (2006). Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a world of strangers. New York: WWNorton & Co.

Arasaratnam, L. A. (2011). Perception and communication in intercultural spaces. Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

Arasaratnam, L. A. (2012). Intercultural spaces and communication within: An explication. Australian Journal of Communication, 39(3), 135–141.

Bredella, L. (2002). What does it mean to be intercultural? In G. Alred, M. Byram, & M. Fleming (Eds.), Intercultural experience and education (pp. 225–239). Clevedon, England; Buffalo [N.Y.]: Multilingual Matters.

Davidson, L., & Pérez Castellanos, L. (2019). Cosmopolitan Ambassadors: International exhibitions, cultural diplomacy and the polycentral museum. Wilmington, Delaware: Vernon Press.

Delanty, G. (2006). The cosmopolitan imagination: critical cosmopolitanism and social theory. The British Journal of Sociology, 57(1), 25–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2006.00092.x

Delanty, G. (2011). Cultural diversity, democracy and the prospects of cosmopolitanism: a theory of cultural encounters. The British Journal of Sociology, 62(4), 633–656. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2011.01384.x

Gupta, A. S. (2002). Changing the focus: A discussion of the dynamics of the intercultural experience. In G. Alred, M. Byram, & M. Fleming (Eds.), Intercultural experience and education (pp. 155–173). Clevedon, England; Buffalo [N.Y.]: Multilingual Matters.

Perry, L. B., & Southwell, L. (2011). Developing intercultural understanding and skills: Models and approaches. Intercultural Education, 22(6), 453–466.

Ryan, P. M. (2002). Searching for the intercultural person. In G. Alred, M. Byram, & M. Fleming (Eds.), Intercultural experience and education (pp. 131–154). Clevedon, England; Buffalo [N.Y.]: Multilingual Matters.

About Lee Davidson

About Lee Davidson

Dr Lee Davidson has 20 years’ experience as a teacher and researcher at Victoria University of Wellington, where she is part of New Zealand’s leading programme in museum and heritage studies. Her work is firmly grounded in theory and practice and she has built close collaborative relationships with key national and international cultural institutions, particularly the Museum of New Zealand, Te Papa Tongarewa. She is an experienced facilitator of workshops and symposia for museum and heritage professionals and also works as a research consultant for external organisations. She regularly presents at international conferences and has published widely on visitor studies, intercultural practice, museum diplomacy, international exhibitions and heritage tourism.

Link: polycentralmuseum.com

About Leticia Pérez Castellanos

About Leticia Pérez Castellanos

Leticia Pérez-Castellanos is a professor at the Escuela Nacional de Conservación, Restauración y Museografía del Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH) in México, where she coordinated the Post Graduate Studies Program in Museology and obtained her Master’s Degree. Her focus is on visitor studies and international exhibitions. She was the Coordinator of Visitor Studies at the Interactive Museum of Economy (MIDE), before becoming Deputy Director of International Exhibitions at INAH. She collaborated with the Ibermuseos Program in the implementation of the Observatorio Iberoamericano de Museos. She is a key actor in strengthening the visitor studies field in Latin America, encouraging professionalization and publications in Spanish.

Link: polycentralmuseum.com

International touring exhibitions have become a regular fixture at major cultural institutions across the globe. They are, perhaps, the most complex, large-scale, expensive and specialised work in contemporary museums. Despite their growing popularity, investment and professionalisation, surprisingly little research has been undertaken to better understand why and how international exhibitions are organised, and what value they have. This article presents new ideas about international exhibitions that have emerged from our extensive research on the subject, recently published in the book Cosmopolitan Ambassadors: International exhibitions, cultural diplomacy and the intercultural museum (Davidson & Pérez Castellanos, 2019). In this book we envisage international exhibitions as mobile contact zones that operate across not only geographical and cultural borders, but also on the boundaries of museum practices. With international exhibitions, it is not only objects that are mobile, but also people—the museum professionals who negotiate, develop and tour these exhibitions in collaboration with international colleagues—who must often negotiate complex political, institutional and museological differences. Likewise, the visitors arriving to see the exhibitions engage with them through the lenses of their own particular contexts. Furthermore, these exhibitions form part of the transnational work of museums which is implicated in systems of international cultural relations and politics. Their meaning and intentions relate, therefore, not only to museum missions, visitor attraction and enlightenment, but also to national and international diplomatic agendas. These forms of encounter and associated interpretations shift as exhibitions move between different cultural contexts. A main premise of our book is that international exhibitions involve myriad forms of cultural encounter and therefore countless opportunities for misunderstanding and mis-representation but, at the same time, significant potential for developing intercultural skills, understanding and what is referred to as a cosmopolitan imagination or outlook—deemed by many as essential for navigating the accelerating processes of globalisation within which we find ourselves in the twenty-first century. At the heart of Cosmopolitan Ambassadors is the tentative proposition that international exhibitions are a means by which museums might represent and advance a cosmopolitan agenda on the world stage. This article explains where our ideas have come from, before outlining what we mean by cosmopolitanism and why we think it is a useful way of thinking about the purpose, practice and potential impact of international exhibitions. We then briefly summarise the main takeaways from our research.We conducted fifty-one interviews with […] curators, concept developers, project managers, writers, interpreters, and educators.

Where have our ideas come from?

Our ideas about cosmopolitanism and international touring exhibitions have evolved from a close study of current museum practice. This has taken the form of a long-term research project focused on two travelling exhibitions involved in an exchange between Aotearoa New Zealand and Mexico. E Tū Ake: Standing Strong was a ground-breaking Indigenous exhibition featuring both traditional and contemporary taonga (Māori cultural treasures) and developed to tour internationally by the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (Te Papa). It was shown briefly in Aotearoa New Zealand before travelling to the Musée du Quai Branly, Paris, followed by the Museo Nacional de las Culturas in Mexico, and finally the Musée de la Civilisation, Québec, Canada, between 2011 and 2013. The hosting of E Tū Ake in Mexico constituted the first phase of the inaugural exhibition exchange between the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH) and Australasia. The second phase involved the development of the exhibition Aztecs by Te Papa in collaboration with INAH, and as part of a partnership with two Australian museums. Aztecs opened at Te Papa in September 2013, and then toured to Melbourne Museum and the Australian Museum in Sydney, before closing and returning to Mexico in February 2015. Aztecs involved a high level of institutional collaboration during the exhibition development stage and engaged staff across the executive, administrative and operational levels of several museums in three countries with contrasting museological, institutional and political contexts. At its centre was an ongoing relationship: the closure of Aztecs and the return of the collection to Mexico marked the end of a cycle of approximately six years of collaborative work between Te Papa and INAH as part of the exhibition exchange. We conducted fifty-one interviews with museum professionals from Mexico, Aotearoa New Zealand and Australia who were closely involved in the production and touring of the exhibitions, including curators, concept developers, project managers, writers, interpreters, and educators. We wanted to understand how professionals in various roles from different countries worked together to develop and manage the exhibitions, the main challenges they faced and how they perceived the exhibitions’ purpose and importance. We also conducted eighty-six in-depth interviews with visitors to gain insights into their cultural encounters with international exhibitions, both short-term and long-term. This aspect of the research was informed by a rapidly expanding theoretical literature on the ways in which visitors engage in complex acts of interpretation and meaning-making when visiting museums and other heritage sites.

Some of the key questions we sought to answer were: How are museums working internationally through exhibitions? What motivates this work? What are the benefits and challenges? What factors contribute to success? What value does this work have for audiences and other stakeholders? What contribution do international exhibitions make to cultural diplomacy, intercultural dialogue and understanding and how can this be assessed?

We conducted fifty-one interviews with museum professionals from Mexico, Aotearoa New Zealand and Australia who were closely involved in the production and touring of the exhibitions, including curators, concept developers, project managers, writers, interpreters, and educators. We wanted to understand how professionals in various roles from different countries worked together to develop and manage the exhibitions, the main challenges they faced and how they perceived the exhibitions’ purpose and importance. We also conducted eighty-six in-depth interviews with visitors to gain insights into their cultural encounters with international exhibitions, both short-term and long-term. This aspect of the research was informed by a rapidly expanding theoretical literature on the ways in which visitors engage in complex acts of interpretation and meaning-making when visiting museums and other heritage sites.

Some of the key questions we sought to answer were: How are museums working internationally through exhibitions? What motivates this work? What are the benefits and challenges? What factors contribute to success? What value does this work have for audiences and other stakeholders? What contribution do international exhibitions make to cultural diplomacy, intercultural dialogue and understanding and how can this be assessed?

International exhibitions are intercultural spaces

What is a cosmopolitan outlook and what does it mean for international exhibitions?

Cosmopolitanism has a long tradition in the history of ideas, and many strands. In the context of international exhibitions, we found British sociologist Gerard Delanty’s (2006, 2011) theory of critical cosmopolitanism particularly helpful. Delanty is interested in what happens when one culture meets another and his cosmopolitan perspective highlights the transformational, creative and critical outcomes of these encounters. Underlying a cosmopolitan perspective or outlook is a “critical self-understanding” and the ability to incorporate the perspectives of others into one’s own “identity, interests or orientation in the world” (Delanty, 2011, pp. 634–635). Essentially, he says, cosmopolitanism is “a way of imagining the world” that suggests both openness and fragility, “since it rests on the bonds of mutuality and dialogue” (Delanty, 2011, p. 635). What does cosmopolitanism look like? Delanty (2006, pp. 42–43) suggests we may find it in:

What does cosmopolitanism look like? Delanty (2006, pp. 42–43) suggests we may find it in:

- irony (emotional distance from one’s own history and culture)

- reflexivity (the recognition that all perspectives are culturally conditioned and contingent)

- scepticism towards the grand narratives of modern ideologies

- care for other cultures and an acceptance of cultural hybridization

- commitment to dialogue with other cultures; and

- nomadism (a condition of never being fully at home in cultural categories or geo-political boundaries).

A comprehensive and cohesive intercultural engagement strategy

Cosmopolitan takeaways for international touring exhibitions

Cosmopolitan Ambassadors presents several practical takeaways that might inform the successful development of international touring exhibitions and an evolving intercultural museum practice. Investigating how our case study exhibitions were organised, and some of the issues faced, demonstrated the importance of clearly understanding the available economic and production models for international exhibitions, and the forms of partnership these might involve. Each model has certain advantages and disadvantages, an awareness of which could enhance decision-making, reduce potential conflicts and misunderstandings, and help institutions to develop better strategies and plan partnerships that are most appropriate to their needs, resources etc. Successful cross-cultural collaboration on international exhibitions requires museum professionals to develop an intercultural museum practice underpinned by a cosmopolitan outlook. This includes a thorough understanding of different working styles, processes and timeframes, as well as appropriate communication styles, channels and frequency. Attention to these helps ensure that staff working across differences can find intercultural solutions to common problems. This may involve re-evaluating their existing practices and the assumptions that underpin them, considering the benefits of adaptation and compromise, adopting open-mindedness, being respectful and receptive to the feelings and needs of others. Intercultural solutions take time and require willingness to talk through differing perspectives in order to create a new centre on what may have previously been a boundary, but the outcome can be innovation, creativity and transformation on both a personal and professional level. Fostering and maintaining strong intercultural relationships is also critical to success in international exhibitions. Culturally specific formal protocols and informal practices for welcoming and hosting visiting staff can be deeply beneficial for enhancing working relationships and long-term connections. Developing intercultural exhibitions requires careful consideration of various display strategies in order to successfully mediate and translate cultural meanings for different audiences. Particular challenges can arise around engaging audiences at the host venue while maintaining cultural sensitivity towards the country of origin. A comprehensive and cohesive intercultural engagement strategy, including object selection, design, text, graphics, marketing, community outreach, events, programming, merchandising and other commercial components, can help to mitigate potential issues. Allowing adequate time for consultation with institutional partners is also crucial in order to overcome inevitable misunderstandings and achieve cosmopolitan outcomes. Where exhibition co-development is involved, and even for less intensive adaptations, the translation of meanings between cultures can require extensive consultation. Reaching intercultural solutions requires a back-and-forth dialogue and this needs to be allowed for in production timelines.

Our research explored in detail the experience of visiting international exhibitions, revealing how visitors connect with the cultural other, negotiate differences and create cosmopolitan and counter-cosmopolitan meanings. We also discuss the resonances and ripples of meaning through visitors’ recollections many months after their initial visits. Understanding the ways in which visitors engage with other cultures in exhibitions can inform a design that helps facilitate these processes, allowing for different styles and preferences, as well as varying levels of intercultural competency and degrees of cosmopolitanism. Recent theories of visitor meaning-making, including affective and embodied cosmopolitan understandings, and the new concepts of intercultural mimicry and polycentral identification developed from our findings, could inform all aspects of exhibition design, marketing and events, complementing what many staff already understand intuitively. Knowing how visitors find relevance and relate exhibition themes to their everyday lives is also informative in regard to wider questions such as the value of international exhibitions, how they might be promoted and their role in cultural diplomacy.

Developing intercultural exhibitions requires careful consideration of various display strategies in order to successfully mediate and translate cultural meanings for different audiences. Particular challenges can arise around engaging audiences at the host venue while maintaining cultural sensitivity towards the country of origin. A comprehensive and cohesive intercultural engagement strategy, including object selection, design, text, graphics, marketing, community outreach, events, programming, merchandising and other commercial components, can help to mitigate potential issues. Allowing adequate time for consultation with institutional partners is also crucial in order to overcome inevitable misunderstandings and achieve cosmopolitan outcomes. Where exhibition co-development is involved, and even for less intensive adaptations, the translation of meanings between cultures can require extensive consultation. Reaching intercultural solutions requires a back-and-forth dialogue and this needs to be allowed for in production timelines.

Our research explored in detail the experience of visiting international exhibitions, revealing how visitors connect with the cultural other, negotiate differences and create cosmopolitan and counter-cosmopolitan meanings. We also discuss the resonances and ripples of meaning through visitors’ recollections many months after their initial visits. Understanding the ways in which visitors engage with other cultures in exhibitions can inform a design that helps facilitate these processes, allowing for different styles and preferences, as well as varying levels of intercultural competency and degrees of cosmopolitanism. Recent theories of visitor meaning-making, including affective and embodied cosmopolitan understandings, and the new concepts of intercultural mimicry and polycentral identification developed from our findings, could inform all aspects of exhibition design, marketing and events, complementing what many staff already understand intuitively. Knowing how visitors find relevance and relate exhibition themes to their everyday lives is also informative in regard to wider questions such as the value of international exhibitions, how they might be promoted and their role in cultural diplomacy.

International exhibitions […] are always in the process of becoming